The incredible (unsolved) mystery of Kaspar Hauser

5 min read

Nuremberg, May 26, 1828: a mysterious boy, about 16 years old, wanders in search of the Captain of the 4th Esgataron of the Shwolishay regiment, to whom he has to deliver a letter. Obviously, no citizen of Nuremberg is aware of the boy’s identity.

The letter explains that, from 7 October 1812, the boy had been entrusted to the mysterious author and, among other things, instructed the captain that “…if he isn’t good for anything [the captain] must either kill him or hang him in the chimney.”

Apparently Kaspar Hauser, this is the boy’s name, was educated in the Christian religion, but he had never been allowed to take a step outside the room where he lived.

Kaspar also brings with him another letter, written by his mother to entrust him to the new “tutor”.

In this letter, Kaspar’s name is revealed, but also his presumed date of birth, April 30, 1812, and the fact that his father was drafted into the cavalry.

The second mystery of Kaspar is linked to these two letters which, following expert reports, are written by the same hand, a detail that is quite improbable, according to what is written on them, and which has led to the hypothesis that the author was in reality the young man.

Kaspar, who was about sixteen years of age, and appeared unable to communicate, with his eyes red and unused to sunlight, is then taken to Captain von Wessing, who directs him to the local police station.

Here he is questioned, proving to be familiar with money, to be a bit literate and to know some prayers. In the few questions he answers, Kaspar demonstrates an extremely limited vocabulary.

At first regarded as a vagabond and halfwit, he was taken to a prison cell where he was kept while the authorities tried to figure out what to make of him. He could utter only a few phrases, clearly meaningless to him, such as, “I want to be a rider like my father,” and “Don’t know,” which he used to express everything from thirst to anxiety. When handed paper and pen, he wrote “Kaspar Hauser.”

In prison, he was diagnosed with an intellectual deficit, but also with excellent memory and a very rapid learning ability, as well as senses developed to the limit of the superhuman.

One of his peculiar characteristics was his repulsion for any food, especially meat and alcohol, apart from bread and water.

At first it was thought that Kaspar Hauser had grown up in the forest, but during several conversations with the people he is entrusted to, the boy recounted another version of his childhood: apparently, he had grown up in a room a couple of meters long and a large one, completely dark, sleeping on a straw bed and having fun just with some wooden toy animals.

Kaspar also said that every day he found bread and water next to his bed.

He added that, periodically, the water tasted more bitter, which caused him a heavier sleep. On such occasions, he would wake up with the straw of the bed changed and his hair and nails trimmed.

The first time the recluse boy saw the man who was taking care of him was shortly before his release. After learning to stand and walk, and equipped with only these and a rough collection of clothes, Kaspar had been led to Nuremberg market and abandoned there.

The story of Kaspar Hauser became known throughout Europe, in an era greedy for bizarre stories, and some thought to bring him genealogically closer to the Baden family, while others considered him an impostor.

In any case, two months after being discovered, Kaspar went to live with Friedrich Daumer, a local teacher, where he was provided round-the-clock education. He flowered under Daumer’s gentle and compassionate tutelage and there learned to read, write, drawing and even play chess.

The boy had been in town for a year and a half when his story managed to get even weirder, because he was supposedly attacked in Daumer’s home.

He claimed the man who had once held him captive returned and slashed him with a razor, saying something like, “You still have to die ere you leave the city of Nuremburg”.

Several months later, Hauser was shot by a pistol that he accidentally discharged. Both incidents happened to come after he had been accused of lying, leading some to believe that he was harming himself on purpose to generate sympathy.

Also the end of the story is not happy.

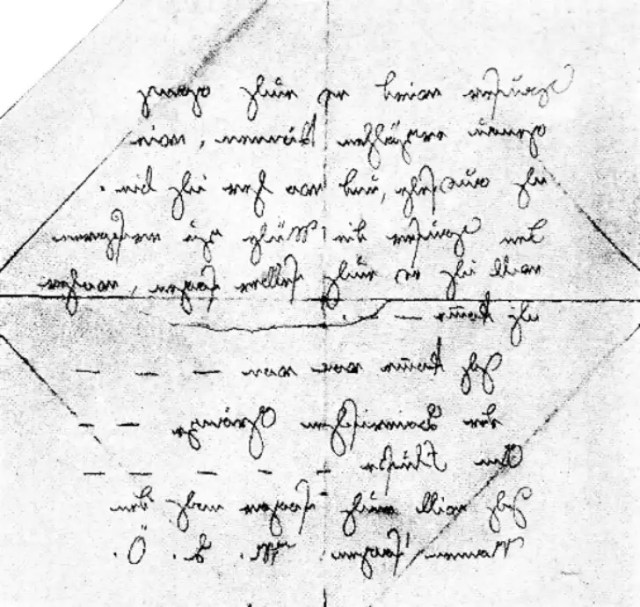

Kaspar died on December 17, 1833, three days after a final incident occurred on December 14, 1833, when Kaspar returned home with a serious chest wound. He said that a stranger had given him a bag, stabbed him in the chest, and fled. The bag contained a note written in mirror writing:

Translation:

Hauser will be

able to tell you quite precisely how

I look and from where I am.

To save Hauser the effort,

I want to tell you myself from where

I come. _ _.

I come from from _ _ _

the Bavarian border _ _

On the river _ _ _ _ _

I will even

tell you the name: M. L. Ö.)

Numerous conflicting explanations have been offered for his murder.

As with the earlier, people believed the wound may have been self-inflicted, and that Kaspar had punctured deeper than he had intended. He may have also written the strange note himself, as the writing itself contained spelling and grammatical errors he commonly made in his own writing.

Anselm Ritter von Feuerbach, a lawyer and criminologist, came to an easy conclusion: Kaspar was the unwanted son of a noble family, how else to explain his imprisonment?

To this day, Kaspar Hauser’s origins remain a total mystery, though the most popular theory has been debunked: Some speculated that Hauser was the lost hereditary prince of Baden. The real prince, son of Charles, Grand Duke of Baden and Stephanie de Beauharnais, supposedly died in 1812 when he was three weeks old.

The theory was that the Countess of Hochberg had the boy hidden away so her own sons could ascend to the throne instead. When the result was obtained, Kaspar was released with the letters he carried with him being written to mask the true reason. Fear that he would eventually expose his perpetrators, however, required his death. However, in 1996, a Hauser blood sample was compared to samples from Baden family descendants. The samples did not match, disproving the theory.

The epitaph on Kaspar’s tombstone in Ansbach, Germany, pretty much sums up his strange, short life: “Here lies Kaspar Hauser, enigma of his time … mysterious his death.”